At the forefront of quality interpreting is a strong ethical practice. Matthew O’Hara reviews the evolution of the RID CPC and relates how individuals can make a difference in understanding and applying its tenets.

The dawn of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) 2013-2016 Strategic Plan and heightened attention on the RID Ethical Practices System (EPS) has brought the perfect time to examine the ethical landscape of our industry. As we look back and look ahead, we cannot plot any course without remembering the value system that guides our profession – ethics. RID founders saw the need to codify a set of ethics that would shape generations of sign language interpreters to come. The minutes of the June 16, 1964 organizational meeting reveal that developing a code of ethics was the second priority listed, with the first aiming to define the purpose of the organization.

Plotting a Course

As the organization embarks on the next 50 years, there is no better time for the consumer and interpreter communities to reflect on the NAD-RID Code of Professional Conduct (CPC). A code of ethics, or Code of Professional Conduct in our case, becomes the stated values that shape our practice and communicate to the public what they can expect of practitioners in the sign language interpreting profession. As we consider the future of the NAD-RID CPC, we must ask ourselves, where have we been? What roadmap(s) did we use to get where we are? Where are we headed? What is our “true north?”

The 2013-2016 Strategic Plan commits our association to the goal of “Strengthen the Ethical Practices System efficiency and consistency in its enforcement of the NAD-RID Code of Professional Conduct.” Furthermore, RID members voted at the 2013 Business Meeting to commission a group of NAD and RID members to strengthen the CPC. How do we accomplish these organization-wide goals and measure our success in achieving them?

Tools For Our Journey

When discussing the CPC, we must agree that a sign language interpreter’s ethical code is the cornerstone of our industry’s standards. Certification means meeting a peer-reviewed measure of one’s knowledge, skills and abilities at the time of examination. Those certified must agree to follow a set of ethical standards. These standards are, in turn, the individuals, and the certification body’s promise to the public. NAD and RID have jointly adopted an ethical code whereby consumers of sign language interpreting services can expect professional conduct consistent with values shared by each organization.

The task for each of us – hearing and Deaf – is to consider the values, and principles that must guide interpreters moving forward. The sun is a critical component in order to calibrate a compass. Perhaps the “sun” for our industry is the values, principles, rules and aspirations articulated in a practitioner’s “compass” which is the CPC.

The Program

In evaluating the EPS program, RID has pulled together statistics on the program since the adoption of the current CPC in 2005. We hope that this data will create a dialogue. Adherence to the CPC is a community-wide priority.

We can analyze the philosophies behind confidentiality, professionalism, respect, and other guiding values. We can talk about how to apply the CPC in various settings and situations. However, let us not forget Aristotle’s “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”. The individual tenets of the CPC are woven together and applied as a whole set of values. Application of one tenet does not occur in isolation. The authors of the current CPC reminded us that the tenets of the CPC “are to be viewed holistically and as a guide to professional behavior.”

As we consider anew the CPC, and what it might look like in the coming years, we need to ask which parts of the CPC are enforceable and which are not. Are some concepts of the CPC more aspirational in nature, and if so, what does that mean in practice? For instance, how does one measure or evaluate “Respect”? We know respect, trust and attitude are highly valued attributes of a sign language interpreter. That said, do we have a shared meaning of professional respect? Does that behavior look the same to everyone? And finally, how is it properly enforced? Interpreters ought to have internalized the core values that drive their work.

Looking Back

Beyond analyzing the ethical landscape of our industry, it is time to take a hard look at the ethics enforcement system, too. It is not solely about what the EPS can do, but what can each of us do. How should each of us respond to clear or perceived breaches of the CPC? We all know that NAD and RID have responsibilities to the public, but we need to challenge ourselves to consider what our personal responsibilities are as individuals – abiding by the intent of the CPC, setting an example, challenging those who stray from the code, and contributing feedback to the CPC review process.

Another area ripe for dialogue is the appropriate consequences for violations. In her article, Sign Language Interpreters: Team Interpreting and its Ethical Consequences, Kelly Decker asked a very important practical question about when we should we avoid teaming with a sign language interpreter who has exhibited unethical behavior? When do we need to go one step farther and report the ethical misconduct? At what point should RID remove an interpreter’s certification? And finally, when does an interpreter deserve to be expelled from the industry?

What Does the Data Show?

Starting in 2013, RID has dedicated more resources to the Ethical Practices System (EPS). Benefits of this renewed commitment to upholding the ethical standards include more timely case management, enhanced customer service, increased public awareness and education, strengthened policies, and program analysis and statistics, with more to come.

As part of the commitment to the EPS program, the EPS staff has begun compiling data to help facilitate informed dialogue. The data compiled here reflects the years following the adoption of the CPC in 2005.

As part of the commitment to the EPS program, the EPS staff has begun compiling data to help facilitate informed dialogue. The data compiled here reflects the years following the adoption of the CPC in 2005.

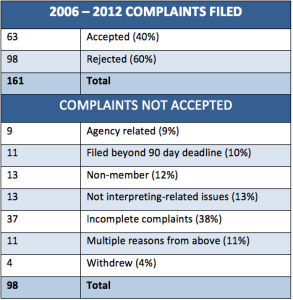

From 2006 to 2012, there were 161 complaints filed with roughly 80% filed by concerned consumers who are Deaf. With over 16,000 members, should we expect more or fewer complaints filed in over a 6-year period? Why or why not? RID recognizes that countless potential complaints may not have been filed because the complainant may not have been aware of the RID EPS, because they knew that their interpreter was not a member or certified and thus the complaint would not have been processed, the consumer may not have known that video complaints can be filed, or other technical barriers. RID is committed to learning more about these barriers and will distribute a survey on this topic.

It is important to note that the average time it took from filing a complaint to resolution was about 7-8 months. This time frame is something that needs careful review moving forward. The integrity of the program must be paramount, including how long cases take to process from start to finish and the resources required.

All complaints are taken seriously and efforts are made to elicit the appropriate information to initiate a formal due process. The RID staff is taking measures to increase access and awareness and is taking the EPS on the road by presenting to stakeholders wherever resources allow. Most importantly, RID is listening and is open to constructive feedback for how the EPS can be more accessible.

The Grievance Process

RID utilizes a grievance system that includes a punitive component and also encourages communication, mediation, the resolution of conflict with a rebuilding of trust and confidence. This process is designed to be both corrective and educational in nature.

RID utilizes a grievance system that includes a punitive component and also encourages communication, mediation, the resolution of conflict with a rebuilding of trust and confidence. This process is designed to be both corrective and educational in nature.

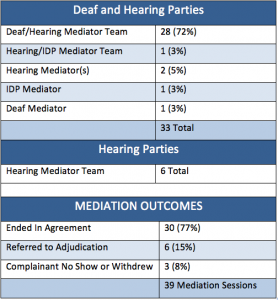

The jewel of the EPS is its mediation program and sincere desire to offer the community legitimate formalized process to come together and discuss allegations of misconduct. If nothing else, the mediators, who are NAD and RID members, assist parties with analyzing the problem themselves. Any agreement must be acceptable to both parties or the complaint is submitted to a panel of adjudicators.

Since the mediation program began in 2000, the mediators have worked mostly in pairs all across the country. Mediators are assigned to cases much like interpreters are matched with consumers – considering the language, culture, backgrounds, and experience of the mediators and matching such with the parties.

Adjudication

The majority of cases are resolved at mediation. Further study is needed about the types of issues brought forth and resolved during mediation to better inform the effectiveness of the CPC.

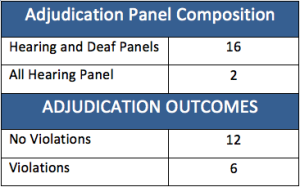

With the majority of cases addressed at the mediation level, only a fraction of cases escalate to adjudication. Since 2006, adjudicators reviewed 18 cases.

To date, there has been no formal study on the correlation between failed mediations and violations at adjudication. This may be a necessary step to assess the effectiveness of the program, examining whether the adjudication phase lacks rigor. Another possibility is that those cases that do not end in mutual agreement at mediation might be where the parties remain at odds and the interpreter is confident that his/her actions were in compliance with the CPC.People have asked why so few violations are published in VIEWS. Most cases do not go beyond mediation because both parties voluntarily agree to and embrace their resolution to the situation. While some might prefer to see more sign language interpreters brought before a jury of peers, the philosophy behind the RID mediation program has always been that the parties should be actively engaged in the EPS process, which often starts with mediation.

To date, there has been no formal study on the correlation between failed mediations and violations at adjudication. This may be a necessary step to assess the effectiveness of the program, examining whether the adjudication phase lacks rigor. Another possibility is that those cases that do not end in mutual agreement at mediation might be where the parties remain at odds and the interpreter is confident that his/her actions were in compliance with the CPC.People have asked why so few violations are published in VIEWS. Most cases do not go beyond mediation because both parties voluntarily agree to and embrace their resolution to the situation. While some might prefer to see more sign language interpreters brought before a jury of peers, the philosophy behind the RID mediation program has always been that the parties should be actively engaged in the EPS process, which often starts with mediation.

All adjudication decisions are made solely on the basis of the panels’ judgment. The panelists are experts in ethical decision-making. All adjudicators, hearing and Deaf, are seasoned certified members of RID. The average number of certified years of adjudicators is almost 27 years.

What’s Next?

What’s next is dialogue! How can we ensure the CPC is relevant and reflects the principles and values interpreters and Deaf people consider essential? How can we effectively and responsibly ensure fidelity to the CPC? As leaders in our profession, we must look for strategic ways to move forward. It’s imperative that dialogue happen in every direction – peer to peer, amongst the Deaf community, within affiliate chapters, during regional and national conferences. Be part of the conversation locally, regionally and nationally by any format that works for you – read articles, engage in conversation, share your ideas, and join a committee. The opportunity is here. Please grab your compass and head for the conversations to come!

References

Fant, Lou. (1990). Silver Threads. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc.