Erica West Oyedele presented Missing Narratives in Interpreting and Interpreter Education at StreetLeverage – X | RID Conference 2015. Her presentation explores the lack of diversity within the predominantly White, female field of sign language interpreting and provides a call to action for potential allies.

You can find the PPT deck for her presentation here.

[Note from StreetLeverage: What follows is an English rendition of Erica’s talk from StreetLeverage – X | RID Conference 2015. We would encourage each of you to watch the video and access Erica’s talk directly.]

Missing Narratives in Interpreting and Interpreter Education

Thank you, StreetLeverage, for giving me the opportunity to be here with all of you. This presentation is based on the research I conducted during graduate school that looked into the experiences of African American/Black interpreters, and took into consideration African American/Black Deaf consumers and their experiences with interpreting services. However, my comments today are not just for them. Rather, they are for all of you. Additionally, it is important for me to thank all of the interpreters of color and all of the Deaf people of color who participated in my research study.

Today I want to talk with you about the narratives that I believe are missing from the field of interpreting and interpreter education. Initially, I planned to show a slide that included the demographics of the field of interpreting. Two days ago, I changed that slide because every day this week there has been a presentation that has shown us the demographics of the RID membership. Hopefully, you’ve paid attention as those numbers have been presented. If you were paying attention to the statistics, then you know that approximately 88% of the RID membership is made up of White interpreters. Therefore, the remaining 12% of RID’s membership are interpreters of color. This slide is a representation of our 12%.

If you attended the ITOC (Interpreters and Transliterators of Color) Member Section forum, then you also would have seen as a part of the presentation a slideshow of various interpreters of color. We make up a diverse population. We are from a wide range of backgrounds. We are hearing, Deaf, straight, gay, lesbian, Codas, and so much more. For interpreters of color in our organization there is a wealth of diversity beyond race.

As I mentioned, we’ve already seen the numbers presented to us throughout the conference so that will not be the focus of this presentation. To be quite honest, for those of you who have seen those numbers presented (88% White interpreters and 12% interpreters of color) and responded with surprise, I ask, why? I can tell you that these numbers are of no surprise to the 12% of interpreters of color within RID. The numbers have been the same for many years! Of course there is some small fluctuation in these numbers from year to year, but the percentages have been consistent. So instead of talking again about the numbers, let’s talk about the impact of these numbers. The impact to interpreters of color, consumers of color, and the impact to all of you, our White allies. You notice that it is my hope that you will become our allies.

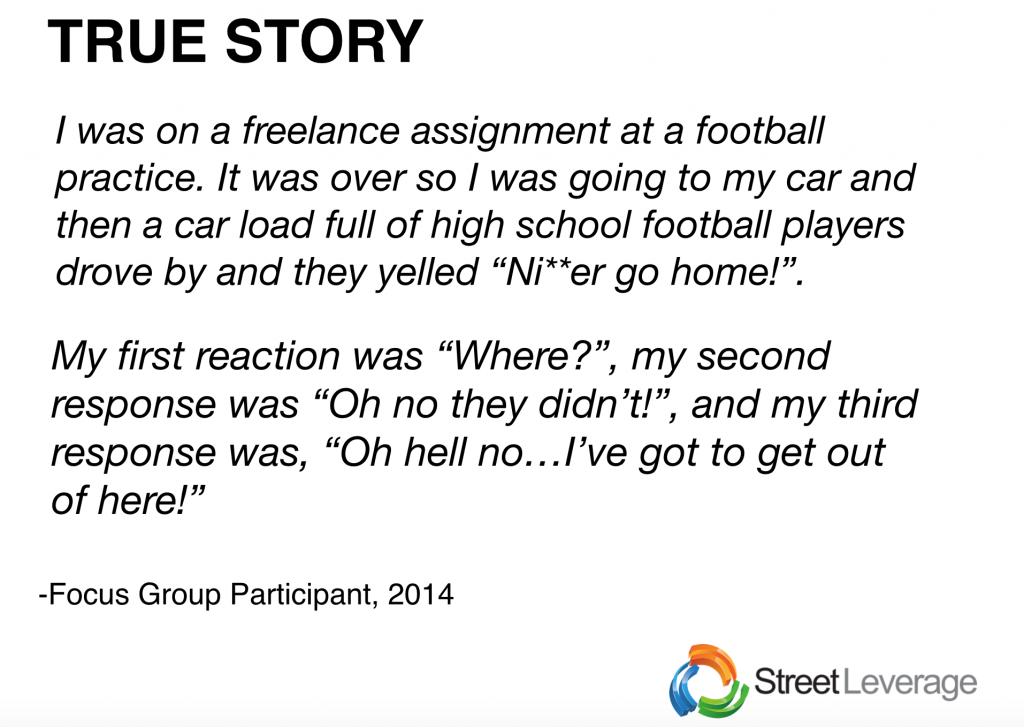

True Story

I want to begin with a story. This story comes from one interpreter who participated in my research study. I have to warn you that this story contains language that will be uncomfortable for you and that’s okay! When you start to notice your own discomfort, breathe in, and then analyze the source of your discomfort. Then we’ll discuss some more.

One of the reasons we are challenged to engage in these types of discussions is because of the fear we hold around this type of topic. I want to let you know that the fear I am referring to extends to me too. Again, that is normal. Right now, my fear has to do with how I will be perceived by my colleagues as a hearing interpreter of color, who has just been sworn in to the RID board. All of those thoughts I recognize right now are a part of who I am. Furthermore, this topic is not easy, yet it is easy for me to become a target when bringing forward this type of discussion. I’ve made the decision that the discussion is important enough that it needs to be addressed.

One of the reasons we are challenged to engage in these types of discussions is because of the fear we hold around this type of topic. I want to let you know that the fear I am referring to extends to me too. Again, that is normal. Right now, my fear has to do with how I will be perceived by my colleagues as a hearing interpreter of color, who has just been sworn in to the RID board. All of those thoughts I recognize right now are a part of who I am. Furthermore, this topic is not easy, yet it is easy for me to become a target when bringing forward this type of discussion. I’ve made the decision that the discussion is important enough that it needs to be addressed.

When you read this story, I want you to recognize that this is the experience of interpreters of color. Although this particular story took place after the interpreter had completed their work, we have to acknowledge that interpreters of color confront systems of oppression before, after, and during their work. What is most unfortunate is that while they are working they often face this discrimination from consumers and colleagues alike. That is the impact of the numbers we have seen but that we have failed to discuss. Perhaps if we have these candid discussions we might come to a place where we would see the number of interpreters of color rise.

When I look at this story, I also recognize the interpreter’s emotional response. Again, it is a normal emotional response, yet I am personally often aware of not wanting to be labeled as the angry (fill in the blank) person: the angry Black person, Deaf person…the angry something! But if we look at what happened, you notice that the interpreter experienced a range of emotions that included confusion and fear, in addition to anger. This is because having to confront systems of oppression becomes an additional demand for interpreters of color. When I speak of demands I am referring to the Demand-Control Schema as presented by Dean and Pollard. Taking into consideration their theory, I think it’s fair to say that interpreters of color have additional demands they have to confront when they go to work. Why isn’t this discussion taking place in interpreter education programs and in workshops in our field? If we truly want to see an increase in the number (or percentage) of interpreters of color, we need to consider what doable actions we might take to acknowledge this reality in our field.

Why Should You Care?

My aim is not for you to read this story and then leave here today feeling sorry for interpreters of color. We don’t want your pity. We want action. Because these stories are not shared in workshops, and because these stories are not shared in interpreter education programs, interpreters of color are not being prepared for the field of interpreting that they will actually face. It also means that the 88% of White interpreters are not learning how to become allies.

Impacts of Power and Privilege

Colleagues

Are interpreters of color really being prepared for the field of interpreting? Are White interpreters prepared to work with us as allies? I don’t know. I think we would be more prepared if we figured out ways to work together. We have to acknowledge the impacts of power, privilege and oppression within this field. The number of African American/Black study participants in my research was 116. 72% shared that they experienced overt acts of discrimination and oppression while they were working. I am no longer talking about before or after work. The majority of Black interpreters experienced oppression from consumers and colleagues at some point while they were working.

Consumers

Participants in the Black Deaf focus group that I conducted also shared their concerns regarding the field of interpreting. We have long discussed in this field the relationship between language and culture. We have acknowledged that for a complete understanding of language to be present, we must first understand the underlying influences of culture. This is not a new discussion for us. Yet, most of the Black Deaf participants in my focus group felt that interpreters did not have an understanding of their culture. Let’s consider what that means for consumers of color. It means they are working overtime to assimilate to the needs of interpreters, instead of interpreters working to accommodate their needs. Interestingly, for the Black Deaf focus group in particular, they overwhelmingly shared that they felt a sense of relief when they had access to interpreters of color. They felt understood. They perceived interpreters of color to be both linguistically and culturally competent. I of course followed up by asking how often they had access to interpreters of color. Every Black Deaf focus group participant said that it was rare for them to have access to interpreters of color.

Mentors/Educators

For those of you who are mentors or educators in this field, the majority of interpreters in my study (around 63%) felt that their mentors and educators were ineffective when it came to discussing multicultural issues or addressing issues of cultural competency. 86 of the participants who were in my study completed a formal interpreter education program. So again, 63% to 64% felt that their instructors were ineffective at addressing issues of multiculturalism or cultural competency. An additional 14% stated that they could not respond to my question because there was no discussion of multiculturalism or cultural competency in their programs at all. Frequently, research participants shared that when discussions of multiculturalism or cultural competency took place, those discussions were limited to Deaf and hearing cultures only. They addressed a Deaf-hearing binary that oversimplifies the two cultural groups, because we know that Deaf and hearing individuals come from a multitude of diverse backgrounds. People of color can be trilingual interpreters, they can be Codas, etc. They have a whole host of identities beyond being hearing or Deaf that impact who they are. That is intersectionality. So when we are not discussing culture beyond the Deaf and hearing binary, we are marginalizing the communities that we serve, we are dismissing who they are, and we are not doing good work.

What Can You Do?

So, perhaps we can’t stop situations like the one I shared with you at the beginning of this talk with the interpreter of color who was innocently walking to her car and confronted discrimination. There is no expectation that we will change the system overnight. But we can start with ourselves. We can start at home!

Allyship Skills

This message is for all of you, the 88%. Develop your allyship skills. Often we use the word ally as a badge, as though it is who we are. I mentioned briefly during the community forum a few nights back a range of different skillsets for allies. On one side, we have avoidance. That’s a skill. You can see oppression happening around you and choose to do nothing. On the other side, we have allyship, which means actively doing anti-oppression work.

Build Cultural Competence

Develop your cultural competence. I realize many people don’t know what that means. I’ve seen many different frameworks that help to describe cultural competency. I have not included that information in this presentation for the sake of time but if you contact me, I am happy to share resources with you. The point is, if you are working with interpreters of color, think about how you are going to connect those interpreters with communities of color. If you are an educator and you are working with interpreters of color, what types of resources are you utilizing in your interpreting program? There are resources out there for you. Are you utilizing the NMIP (National Multicultural Interpreter Project) curriculum to supplement your instruction and as a part of your mentoring resources?

The NCIEC (National Consortium of Interpreter Education Centers) recently released their social justice module for infusion within interpreter preparation programs. Are you incorporating those messages into your curriculum? When you require students to read articles or books, who are the authors? When you invite people of color to come to your classes and workshops to present, do you invite them to discuss race only or do you invite them to talk about the whole of their experiences and who they are? When you extend invitations to people of color, and you only ask them to talk about race, that looks like tokenism to me.

Invest in Social Capital

My closing comment is this. Invest in social capital for interpreters of color. In short, social capital is a term used to describe the quality of relationships people have within a particular group. If you have good, strong, relationships, and you have a large network within your community to interact with, then your social capital is strong. However, if your relationship ties are weak or your network is small, then your social capital is weak. So in your interpreting programs and in the workshops you teach, when you name RID or NAD, make sure you also name NAOBI, name Mano a Mano, name NBDA, name the Asian Deaf Congress, and the many other organizations of color that are out there. Connect interpreters of color with organizations and communities of color, and while you’re at it, check these organizations out for yourself, too. That is a way for you, the 88%, to partner with us.

Thank you.

As the noise of Bourbon Street fades to allow a framing of the developments at the 2015 RID conference held August 8-12th in New Orleans, LA, questions linger regarding the suspension of performance testing. With some time and the visibility sought from the results of the risk assessment expected in November, we hope for greater clarity for the path forward. For more coverage on the credentialing moratorium click

As the noise of Bourbon Street fades to allow a framing of the developments at the 2015 RID conference held August 8-12th in New Orleans, LA, questions linger regarding the suspension of performance testing. With some time and the visibility sought from the results of the risk assessment expected in November, we hope for greater clarity for the path forward. For more coverage on the credentialing moratorium click